In collaboration with Lövendahl, Zakarian created and curated BLACKLANDS:

a group exhibition focusing on the color black.

This interview series continues directing the spotlight at fascinating artists working with the darkest shades.

Hyperrealism Gone Wild: Esben Horn

2 May 2024

The Timeless Beauty in Classical Figurative Art : Xenia von Buchwald

27 June 2024Artist Interview

Inken Stabell

Sublime Nature Drawings and Traditional Printmaking

Interview by Mariam Zakarian, May 2024.

Interviewet findes også på dansk.

There is a concept I was introduced to back when I studied Art History at Stockholm University, which was particularly significant for my own creative aspirations: The Sublime.

Although the concept has existed at least since Ancient Greece, sublimity was defined by Edmund Burke in 1757 as an impossible greatness, producing the strongest emotion the mind is capable of feeling. Unlike beauty, the sublime is not just comfortable or pleasant, it is much greater. Something, that strikes awe and terror into the heart of the viewer. But because there is no real threat, and the mind is experiencing the effect vicariously, the result is thrilling and exciting.

An appropriate word to describe the works of this month’s artist: Inken Stabell.

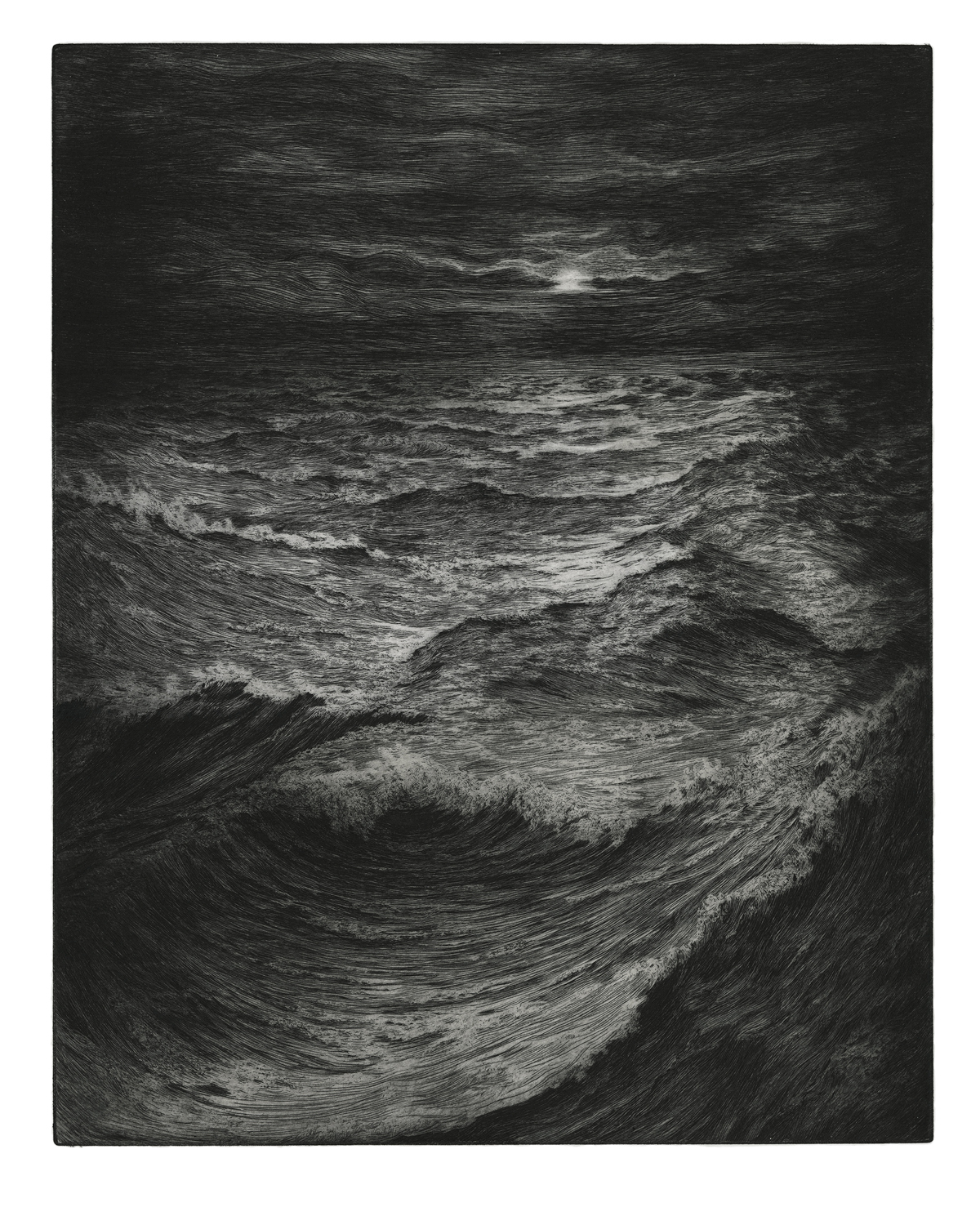

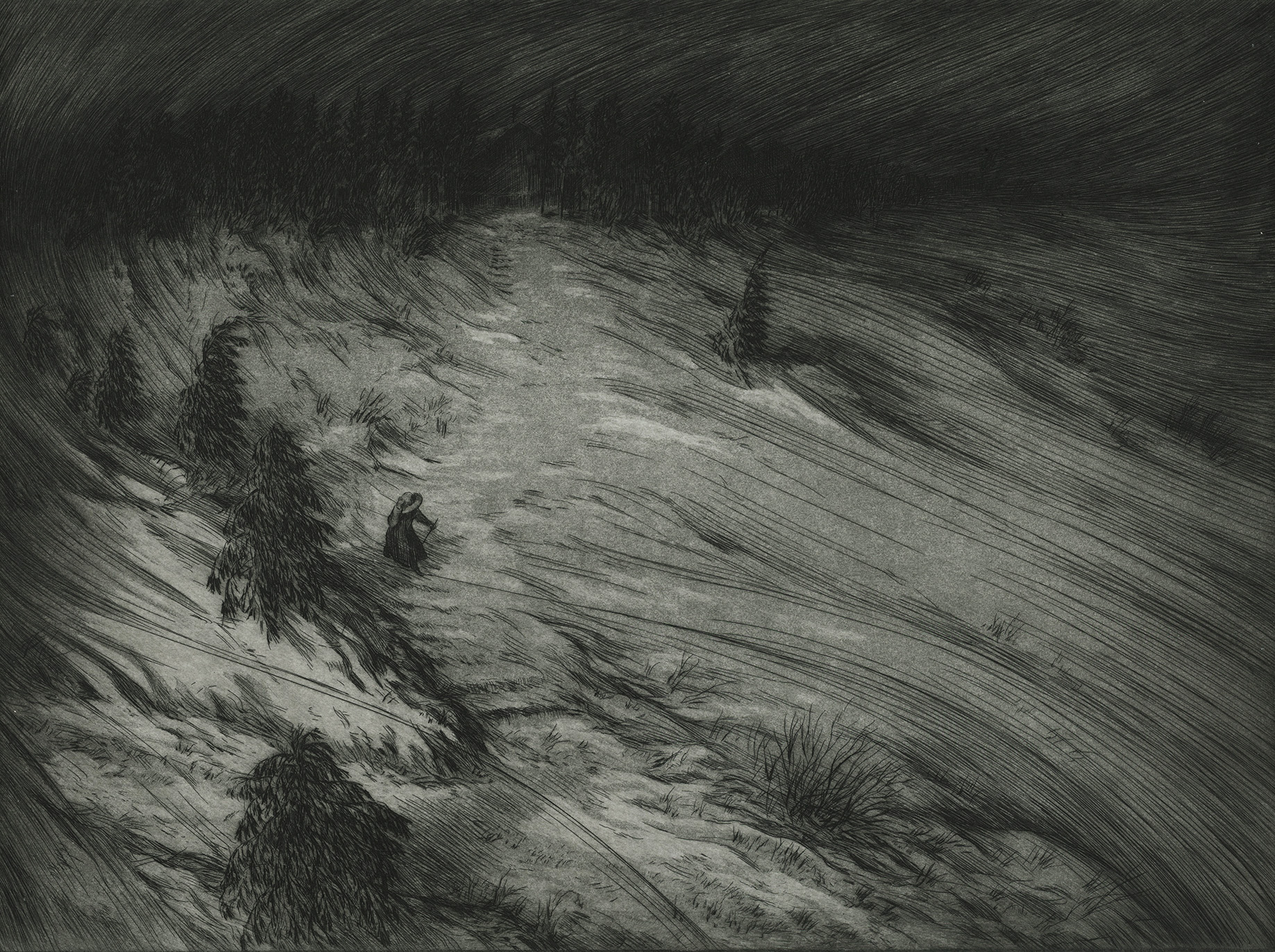

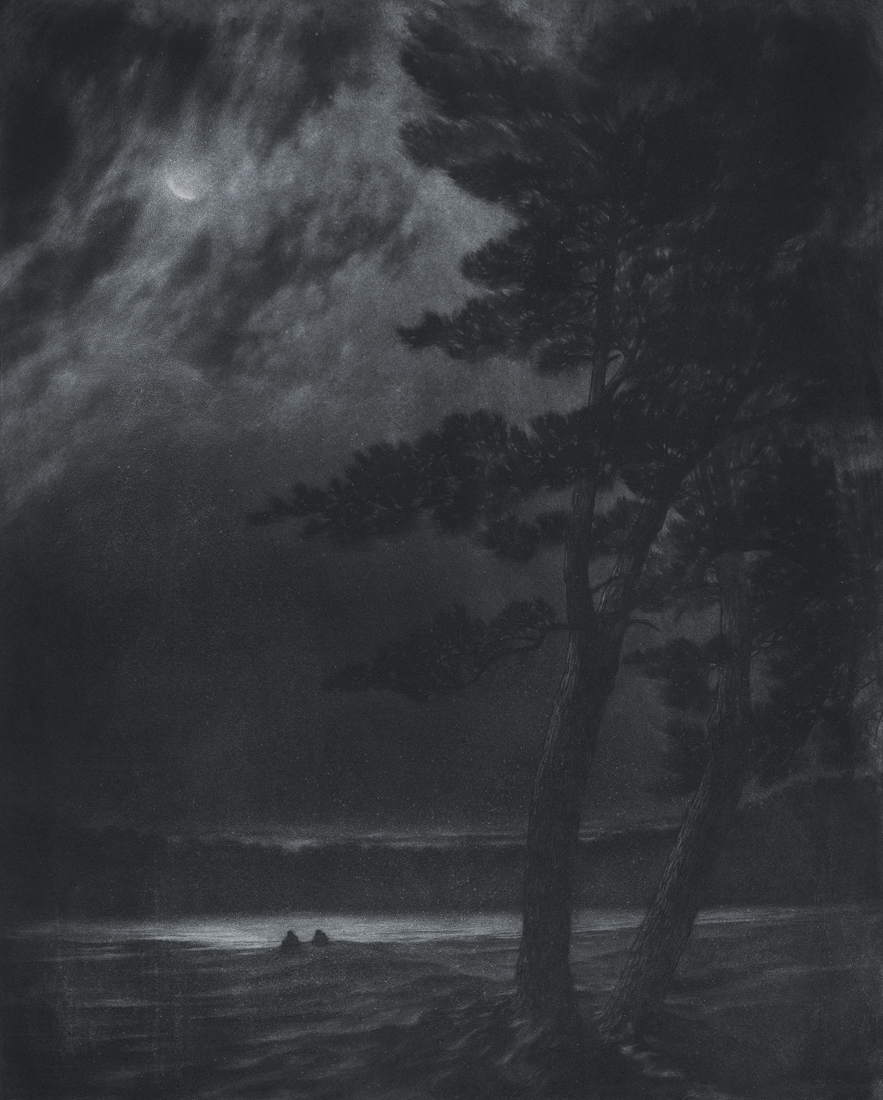

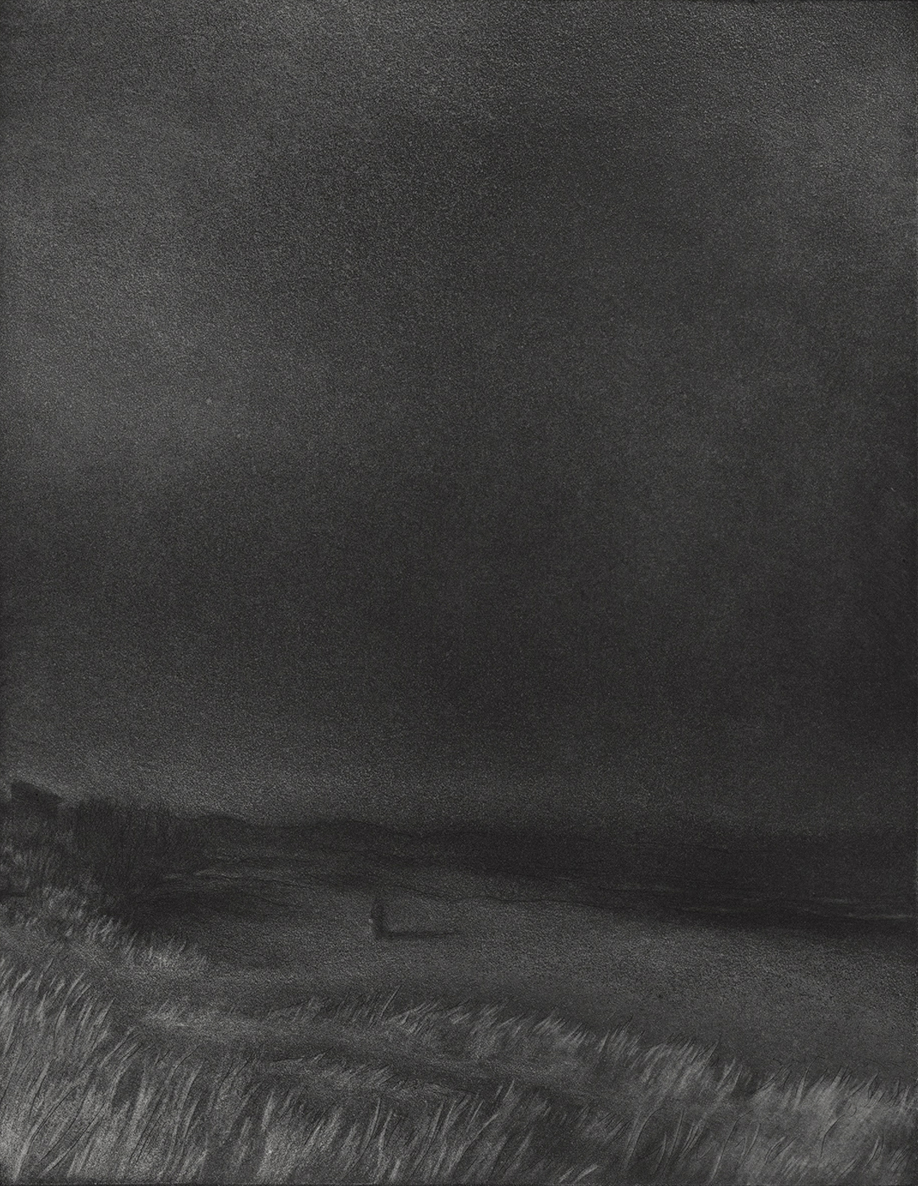

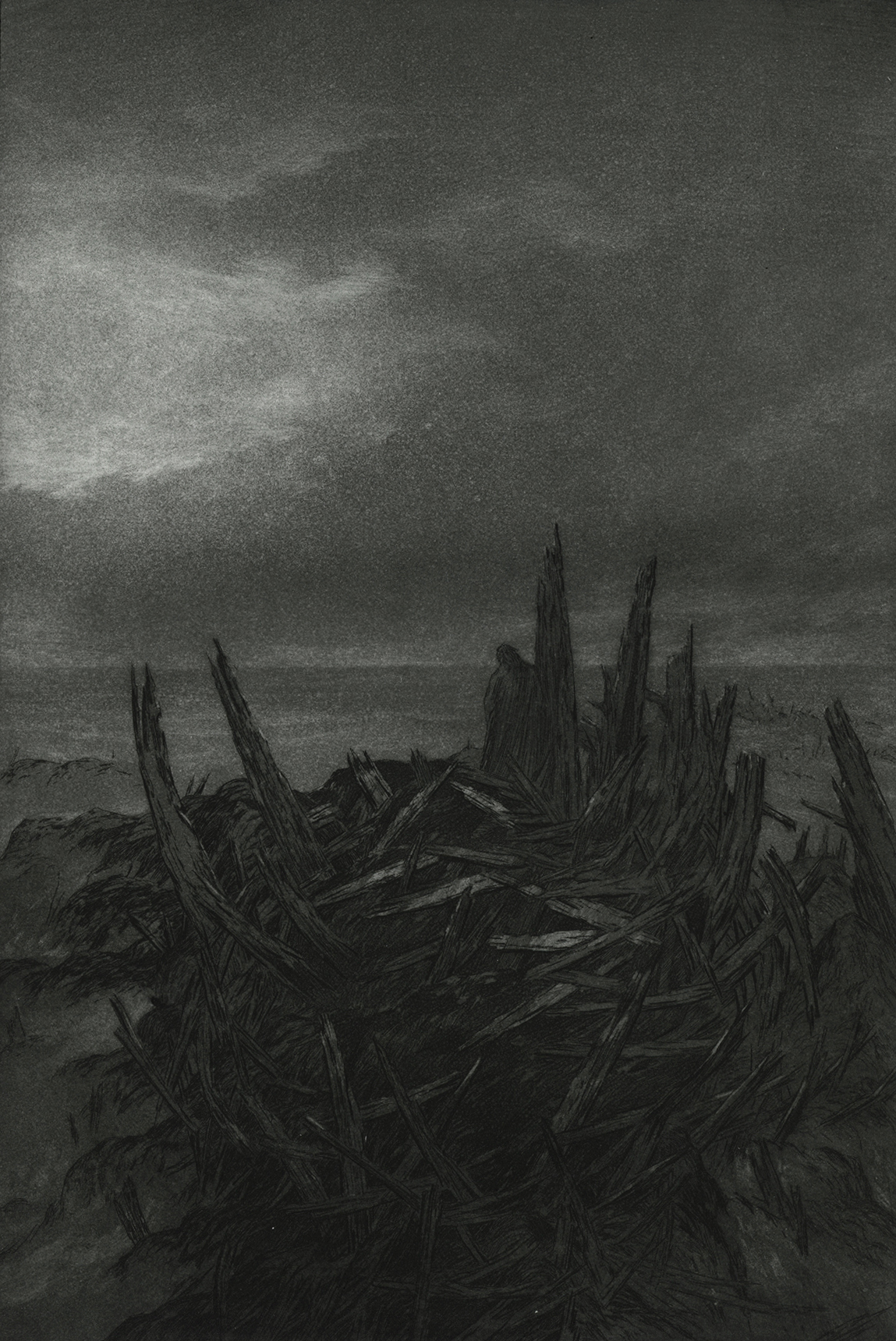

Moonkissed, melancholic landscapes, vast and endless. Violent, churning waves. Bottomless, horrifying waters and merciless storms.

Even the comparatively peaceful landscapes feel brutal the more you look, as a lone wanderer travels towards the horizon surrounded by snow and nothing.

Sublime. Sinister, but thrilling.

The first time I encountered Inken Stabell’s art was on Twitter. The dramatic pieces instantly captivated me, reminding me of eras in aesthetics that are among my personal favorites. Back when exceptional craft was not dismissed so easily, and cute gimmicks alone could not pass for high art. The fine technical and creative skills necessary to conjure up these works are obvious and non-negotiable.

Stabell is an independent printmaker and illustrator from the north of Germany, who has a background in classical realism, contemporary illustration research and forest ecology. She occasionally teaches at the Swedish Academy of Realist Art and uses etching to produce her remarkable, atmospheric landscapes.

Etching is a traditional hand-printing technique dating back to at least the 1500s. A flat printing plate, made of usually copper or zinc, is first covered with an acid-resistant protective substance. The artist then meticulously carves the image on this protective coat with an etching needle or similar tool, exposing the metal underneath. The plate gets submerged in acid, which eats at only the exposed metal parts, sinking the drawing into the plate.

When the plate is then covered in ink, the color will go into all of the fine grooves in the metal that make up the image. Although excess ink is wiped off the plate, the grooves still contain pigment.

Printing paper is put onto the surface of the carved metal plate and compressed by a heavy roller, so that the ink from the grooves stains the paper, producing the print. The plate is re-inked by hand for each print.

Additionally, tonal effects can be produced by spraying thin, acid-resistant layers onto the metal plate before it’s submerged in acid, creating grainy, sunken areas which hold the ink in subtle gradients, resembling watercolor drawings. This technique is called aquatint and Stabell uses it together with etching to achieve her complex, detailed compositions.

The prints are made more beautiful still by the fact that no two are completely identical. When hand-producing prints like this, there will always be micro-variations, small differences in texture and tone.

Despite the authenticity in relying on craft, using these antique techniques and honoring classical aesthetics, Stabell’s work is not just a throwback to earlier European art. The minimalism in some of these compositions reminds me of Japanese visual traditions and the liberal incorporation of graininess and texture feel very contemporary.

Read on for insights into Inken Stabell’s gorgeous, powerful art and creative journey.

"It's a quiet sort of art.

Quiet but not silent, like nature."

- Inken Stabell

Q: Not many people make this kind of art anymore. What is it about these classic techniques and aesthetics that appeals to you the most?

Inken Stabell: I think in classical drawing there is an inherent beauty in the fact that someone just decides to spend months to capture something on paper in an objectively high quality. The passing on of techniques, the exact description and further development of the process make this form of art a learnable and rational thing which isn’t dependent on subjective perception. That also means you can’t hide behind pretty words if you’re lacking in technique; it’s an honest reflection of what you can and can’t do. For me that’s what makes it one of the most approachable forms of art.

Q: When and why did you start drawing the way you do now?

I started out with just coloured pencil illustrations as a teen and then moved on from there to watercolour and ink, then eventually I tried etching in 2017. The moody landscapes started in 2014 for me. Somehow that suddenly really felt like my own aesthetic, although I thought it was just a one-time experiment then.

Q: Have you gone to art school or taken courses?

How did your current techniques and style develop?

I went to an atelier school to learn realistic drawing skills once I realised that relying only on style can get you only so far, like I hit a wall where my skill was lacking. My work was already moody but more on the expressive side, then with the realism training I was able to add more well-rendered areas into my pictures.

Today I use the expressive stylistic edge more intentionally and sparingly, but it’s still the thing that makes my style more illustrative and not purely realistic. The classical techniques were a well-needed upgrade, but not the end goal.

"You can't hide behind pretty words

if you're lacking in technique;

it's an honest reflection of what you can and can't do.

For me that's what makes [classical drawing] one of the most approachable forms of art."

- Inken Stabell

Q: Does your work arise intellectually or intuitively? Do you work from a philosophy or artist statement?

I do research for some interesting themes to illustrate, but the work itself always starts intuitively. Since I aim for a strong first visual impression and mood, letting an image form and change in my head until it leaves a strong impact is the most reliable way to find something worth drawing.

Generally I think the statement should follow the work, not the other way around. If I start a long-term project with multiple artworks, I leave myself enough creative space for each single piece.

Q: Are there themes in your work that you keep returning to?

Mostly landscapes and seascapes. Must be the escapist in me. Figurative work is fun too, but I love that a landscape can simply invite you into its world without needing to say anything or show anyone in particular.

It’s a quiet sort of art. Quiet but not silent, like nature.

Q: How come you chose nature motifs as your focus? Are they mostly imaginary or do you base them on your own time spent in the wild?

Most of my landscapes and seascapes are imaginary, but the overall vegetation and vibe is from my own memories from the nature around Berlin and the North Sea coast. I’ve been trying to describe what it is about landscapes that I can capture through them which I can’t with figurative illustrations. I think it has to do with the openness towards the viewer, as in they (that includes me) see the picture and can fully focus on the experience of a highly stylised landscape where everything is arranged to maximum atmospheric effect. Any specific people doing any specific actions in those landscapes would often only distract from that.

Q: Who and/or what are your main influences?

A few names would be Walter Leistikow, Kawase Hasui, Theodor Kittelsen and Horst Janssen.

I’m also following a lot of contemporary traditional and digital illustrators who have developed some brilliant original styles. I’m very grateful for the online art community, we all inspire each other to get better.

Q: Do you draw in silence or listen to something?

My pictures might not look like it, but I’m practically partying through the process. I always listen to something. Whatever I’m into at the time, usually some weird prog metal, but I have a few albums that I put on whenever I need to carry myself through hours of labour and keep up the energy.

Q: Why do you choose to use black in your work?

It kind of went from low use of colour in drawings to just black when I switched to etching primarily. Adding colour there complicates the whole process and I’m now only starting to experiment with that. However, I’m generally a fan of black and white art, as there is a certain calmness in the absence of colour thanks to less tonal contrast and it lets you focus more on the structural aesthetic of an image.

Q: Is there an area in art that you want to improve in?

I want to learn more from painters, their approach to build up an image through shapes and plains rather than constructive lines. It’s a completely different mindset from the beginning and I feel like there’s a lot I haven’t understood yet.

Q: Do you have a dream project that you would undertake if you had unlimited time and resources?

Apart from wanting to make bigger and bigger artworks, I’m not sure…. More sequential original art would be fun, that definitely seems risky without funding.

"I love that a landscape can simply invite you into its world

without needing to say anything or show anyone in particular."

- Inken Stabell

Q: Do you have any experiences with censorship? What do you think about it and how does it affect your

work?

I’ve never run into such issues and would honestly be very surprised if that ever happened since I basically just draw pretty landscapes. The only thing I can maybe think of is that the craft-driven approach I have is often called banal in the institutional art world and thus it’s hard to find recognition there, but I’ve learned to just focus on my work instead.

Q: What do you wish you knew when you started making art?

That the whole realistic drawing thing even exists today. That people still dedicate their life to improving at this craft and that you can learn from them. It simply wasn’t a thing in Germany when I started. I’m glad I started in the early internet forum days, though, and then learned from the wonderful community of concept artists when I found them online.

Q: Art is notoriously difficult to define and there are many disagreements. How would you define art?

The very loose definition of today is fine to me, even if it gets exploited occasionally. The exact distinction between art and craft was never made and there’s maybe not really a point in doing that since beautifully crafted things can get appreciated simply for the fact that they have been made.

In any case, it has to be human made. Do not call AI output art.

Q: And finally, why do you create art?

The joy of creating something original and also wanting to get better at it is pretty common human nature. I think most people can relate to that. I just got so addicted and passionate about it that I can’t do anything else anymore… I’ve tried!

Find more of Inken Stabell‘s work on Instagram, on Twitter and on her Website.

Check out last month’s artist interview with Esben Horn about hyperrealistic sculptures of wildlife.

And for more dramatic landscapes, view the Dark Pointillism of Simon Garðarsson